Hello there! Or 01001000 01100101 01101100 01101100 01101111 00100000 01110100 01101000 01100101 01110010 01100101, as those of us compelled to type “hello there” into a binary translator might say. This month’s Tech Trek leads Amber, all hopped up on toy nostalgia brought on by the holidays, to take a look at the history of talking doll technology, while Maggie reviews the time-travel movie masterpiece Primer. So let’s get to it! Or should we say, 01101100 01100101 01110100 00100111 01110011 00100000 01100111 01100101 01110100 00100000 01110100 01101111 00100000 01101001 01110100?

Explore: The Evolution of Talking Dolls

Those of us who played with dolls growing up undoubtedly talked to them or performed “conversations” in which the dolls talked to each other. (I used to pretend my dolls were rowdy guests on seedy daytime talk shows.) But what about dolls that are able to speak for themselves? Since the period right after the Industrial Revolution, toy manufacturers have worked to make dolls that are more and more lifelike, and that offer a more tangible sense of companionship and interactivity, by giving them voices. Here are some of the highlights in the oft-creeptacular progression of talking-doll technology:

Those of us who played with dolls growing up undoubtedly talked to them or performed “conversations” in which the dolls talked to each other. (I used to pretend my dolls were rowdy guests on seedy daytime talk shows.) But what about dolls that are able to speak for themselves? Since the period right after the Industrial Revolution, toy manufacturers have worked to make dolls that are more and more lifelike, and that offer a more tangible sense of companionship and interactivity, by giving them voices. Here are some of the highlights in the oft-creeptacular progression of talking-doll technology:

The Edison Phonograph Doll (1890)

At the end of the 19th century, famed elephant electricutioner (and revolutionary inventor) Thomas Alva Edison used his exceptional intellect to create history’s most horrifying talking doll. Before that, in 1878, Edison patented the phonograph—a machine that records and reproduces sound. When the phonograph was introduced to the world, people were dumbstruck: A machine with the ability to record the human voice was truly unfathomable. A decade later, looking for new ways to use the recently developed wax cylinder phonograph (this was an improvement on the tin-foil cylinder phonograph that Edison initially developed), Edison designed his doll. Inside the doll’s metal torso, Edison placed a phonograph that was operated by a crank sticking out of the doll’s back. When the crank was turned, a voice recorded on the wax cylinder recited well-known nursery rhymes like “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” or bedtime prayers like “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep.” The doll sounded as though it was possessed by a demon—all high-pitched, creaky, and menacing—without actually needing to house an evil spirit, essentially cutting out the middleman:

All kidding aside, Edison didn’t intend for the doll’s voice to be nightmare fuel, but that’s exactly what it was and is to this day. The dolls were a commercial failure—they were only sold for about a month, and Edison himself even started to refer to them as his “little monsters.” Surprisingly, it wasn’t the demonic voice that was so off-putting to consumers—it was the exorbitant price, which would amount to about $200 today. Another factor was that the dolls’ mouths didn’t move when they talked (once befuddled by a simple recording device, people now basically wanted androids).

“Mama” dolls (1920s–1930s)

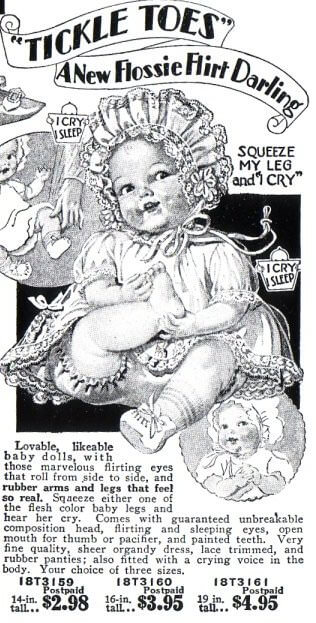

Mama dolls were mega popular in the ’20s and ’30s, drumming up a sort of Cabbage Patch Kids, Tickle Me Elmo, Bratz Doll-esque fervor when they were released. They were referred to as mama dolls because they emitted a whiny, wheezy noise that sounded a bit like a baby crying “mama,” if that baby were a dog’s squeeze toy. The mechanism that made these dolls “talk” was a lot more basic than Edison’s phonograph (it didn’t use recorded audio) and actually had its genesis in 19th century Japan, where the first crying baby dolls were sold. Tucked inside each mama doll’s body was a cylindrical bellows device called a “crier” or a “cry box” that drew in air when the bellows expanded and forced it out when it contracted, in a way similar to an accordion. Depending on the doll, the bellows would be activated by pressing down on the doll or tipping it over.

While one of the selling points of these dolls was their ability to “talk,” the bigger draw was that they were made out of “composition”—a mixture of glue, cornstarch, and sawdust—that made them a lot more durable and flexible than the porcelain dolls of previous eras. Composition, plus the mama doll’s “voice,” equalled new levels of real in doll production!

Chatty Cathy (1959–1965)

Designed by Mattel to be an interactive toy, Chatty Cathy was a talking doll that could say 11 different phrases like, “Let’s play house,” and “Please change my dress.” (Sounds like fun, huh?) The doll’s talking mechanism was activated by a pull-string that hung out of its back. Pulling the string turned a grooved disc inside the doll’s body, and a metal needle produced sound from the disc by traveling through the grooves. Essentially, it was a tiny record player.

Due to advances in recording technology, and the fact that the doll’s voice was provided by legendary voice actress June Foray (aka Rocky the Flying Squirrel, Cindy Lou Who, and Mulan’s Grandmother Fu), Chatty Cathy didn’t sound like the spawn of Beelzebub like Edison’s doll did. Kids loved her, and grown-up baby boomers (like my mom) still have fond memories of the swell times they spent gabbing with Cathy. After Chatty Cathy’s success (she was second to Barbie in popularity at the time), Mattel executives undoubtedly started wringing their hands and cackling diabolically as they plotted their next move: to inundate the toy market with tons and tons of talking dolls (mwuhahaha). Mattel released loads of different talking dolls throughout the ’60s and ’70s, including Baby Small-Talk and Sister Small-Talk (dolls like to keep their convos surface level, OK?).

Jill (1987)

Jill is the first battery-powered doll on this list. She was massive—about the size of an actual child—and designed to be “a lot like you,” meaning that she periodically turned her head slowly from side-to-side and then stiffly moved her arms up and down as she spoke (things that human children TOTALLY do). Even though Jill was definitely a talking doll—her voice-audio was recorded onto a multi-track cassette tape that you’d pop into the back of her body—she was also a legit robot. There were microprocessors inside, making Jill interactive in a way that blew Chatty Cathy out of the water. Jill asked a question, and through the use of a microphone in the doll’s torso and those microprocessors, she detected the response. An audio track that roughly corresponded with what was said to her would then play, creating the illusion that a conversation was taking place. The ’80s were a decade marked by significant developments in microprocessing, as well as widespread hair-perming, so you could say that curly haired Jill was the embodiment of the era.

Telephone Tammy (1994)

Clenching a pink cordless phone in her plastic hand and dressed in a floral, Olsen-twins-circa-Full House jumpsuit, Telephone Tammy is noteworthy for her ability to say hundreds of phrases, including “Hello, I’ve been waiting for your call,” and “Let’s share secrets.” (Yikes!) The doll came with a remote control phone. By pressing its keypad, you could make Tammy move and talk. The implementation of wireless technology is really interesting when you consider that many of the earlier talking dolls required some sort of physical contact with the doll to get it to speak. The idea of talking to a doll on the phone is weird as hell—there may actually be NOTHING weirder. At the same time, it probably could be sort of cathartic telling Tammy about things that you might be afraid to tell real people? Regardless, Telephone Tammy was clearly devised to create a sense of intimacy between the child and the doll and replicate the experience of chit-chatting with your Number One.

My Friend Cayla (2014)

My Friend Cayla has been dubbed “the world’s first interactive doll” by its developers. As this list shows, that claim isn’t really true. The doll does, however, offer a much higher level of interactivity than what’s been available in the past—she’s the culmination of everything that talking doll technology has been building toward. This doll connects to the internet using wireless Bluetooth technology and functions through voice control, like Amazon Echo and Apple’s Siri You can ask the doll questions and, with a reliable internet connection, she can provide you with answers. Because she was released in 2014, she naturally comes with her own app, which you can use to play games with her.

My Friend Cayla elevates what talking dolls are capable of—she has a virtually endless vocabulary and can be used as an educational tool. But her development raises questions about the future of talking dolls. Would pushing this technology any further wind up creating something that could no longer be called a doll? I mean, when does a computerized, interactive doll like Cayla stop being a doll and just become a computer with hair that can be brushed? Does a doll that’s able to interact with a child on the level that Cayla can inhibit imagination? Can Cayla record and save what kids say so that toy manufacturers have even creepier ways to mine their brains for market research? Will people with nefarious intentions hack into Caylas to make her their mouthpiece? (It’s possible: Cayla was already hacked by researchers who made her say a bunch of bad words.) If the past is any indication, toy manufacturers will keep inventing new ways to get dolls to communicate with us, so it probably won’t be long before we get the answers to these questions. —Amber

Movie of the Month: Primer (2004)

“Are you hungry? I haven’t eaten since later today.”

Attention all nerds and/or cinephiles! You gotta see Primer (streaming in the U.S. on Netflix right now)! It’s an indie thriller, beautifully shot on 16mm film, about a pair of engineers who accidentally build a time machine in their garage, and use themselves as test subjects:

Attention all nerds and/or cinephiles! You gotta see Primer (streaming in the U.S. on Netflix right now)! It’s an indie thriller, beautifully shot on 16mm film, about a pair of engineers who accidentally build a time machine in their garage, and use themselves as test subjects:

Primer also is an incredible testament to what you can do with limited means and a great idea: It was made for only $7,000!

Shane Carruth was a mathematics major and software engineer who studied theoretical time travel for years before writing and directing this movie (he also stars in it and composed the musical score). There isn’t a “Regular Joe” character to explain the science in layman’s terms to the viewer, so you’re totally on your own with these physics-spouting characters and this script, which is almost 100 percent scientific jargon. I had to watch the movie twice and read this guide to get the plot completely, but here are the basics…

In the story, the engineers go back in time within their own lifetimes, therefore creating doubles of themselves that could cause massive disruptions to the space-time continuum. (This is a common sci-fi story device called “dynamic” time travel, in which altering events in the past definitely leads to changing or messing up something in the future. It may be best known for its role in the Back to the Future franchise.)

What I really like about Primer is that it addresses a basic question of time travel (“Is it really possible to change the past?”) while also delving into super nitty-gritty details, such as: What if you brought your cell phone to the past, where a double of you also existed—would your phone ring or your double’s? What if you worked with your double to control the outcome of the future? What if you put a time machine INSIDE a time machine? My brain was FRIED by the end of this movie, but I still wanted to go back in time to watch it again for the first time! —Maggie ♦

We’re always down to read and (try our darndest to) answer your tech-related questions, so don’t be afraid to send an email our way. Please write to us at [email protected] with your name, age, city/state, and question.